Canadian whisky is often misunderstood and sometimes not given respect in certain circles. But it is enjoying something of a renaissance lately and if you’re only familiar with the one in the purple bag, you’re really missing out. We’d like to fill you in on the makings of this style of whisky.

First of all, to be called Canadian whisky, the whisky must contain alcohol distillate made from cereal grain that’s mashed and distilled. It must age in small wood for at least three years in Canada. Finally, it must contain no less than 40% alcohol by volume—that’s really about it. This gives Canadian whisky blenders a rare luxury in the whisky world for innovation without excessive restrictions backing them into a corner. If the whisky follows this definition and retains the character, flavors and aromas authorized to Canadian whisky, then it’s time to pour it in a glass.

Why is Canadian Whisky Called Rye?

Canadian whisky doesn’t require rye whisky to call it rye.

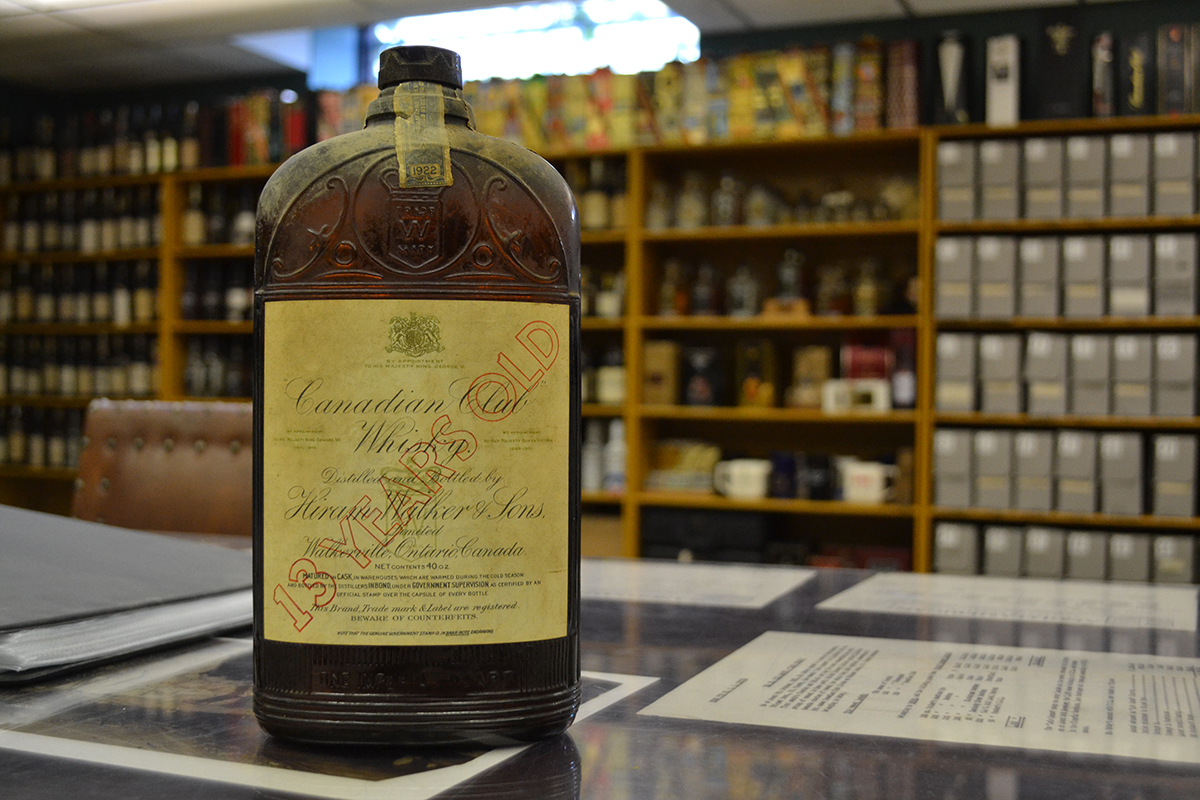

Canadian Club Circa 1922 / Photo Credit: Blair Phillips

Canadian Club Circa 1922 / Photo Credit: Blair Phillips

A long time ago, wheat whisky was king and the grain was abundant. Dutch and German immigrants arrived in Canada and started adding rye grain to the wheat mash. It became so popular that people asked for it as “rye”. Corn later replaced wheat, but the nickname stuck. Some producers have gradually shifted to labelling their whisky “Canadian whisky” but you’ll still hear some Canadians refer to their whisky as rye.

Breaking it Down

There are eight large distilleries and a rapidly increasing micro-distillery scene that make up Canada’s whisky landscape. The big eight are: Valleyfield in Quebec; Hiram Walker, Canadian Mist and Forty Creek in Ontario; Gimli in Manitoba; and Highwood, Alberta Distillers and Black Velvet in Alberta. Since restrictions don’t handcuff Canadian distilleries, it makes pinning down a standardized Canadian whisky process difficult. Each of these distilleries has developed its own whisky production process—but there are some common practices.

Highwood Distillery / Photo Credit: Blair Phillips

Highwood Distillery / Photo Credit: Blair Phillips

The distance between these distilleries is immense. So, similar to single malt scotch, most Canadian whiskies are the product of one distillery. The big eight distilleries generally don’t trade barrels or use someone else’s whisky in their blends. Exceptions are rare. Also, most distillers don’t use mash bills. Instead, they ferment, distill and age each grain individually. These become single grain, single distillery whiskies that they blend after maturation. Exceptions? Crown Royal uses a mash bill for a whisky that’s part of their blending component and Black Velvet ferments and distills each grain separately, blending the spirit prior to aging.

Distillation

Canadian Whisky uses two common distilling methods despite which grain they utilize. The first are base whiskies. Normally, base whiskies are distilled to a high alcohol content, then aged in used barrels. Some distillers make many styles of base whisky, but never grain neutral spirit. Base whiskies span a wide range of ages and can be very flavorful.

Black Velvet Distillery / Photo Credit: Blair Phillips

Black Velvet Distillery / Photo Credit: Blair Phillips

Flavoring whiskies are the second distilling method. These are distilled to a lower alcohol content in column or pot-stills then aged in virgin oak, ex-bourbon or rye re-fill casks. The two methods come together after maturation through skillful blending.

Maturation

Distilling and maturing each grain separately is done for a reason.

The distillery can fine-tune which cask is beneficial based on the grain. These tailored cask types, chars and aging techniques give each grain a specific job within the final whisky. For example, a lightly-toasted barrel will preserve rye’s fruitiness and spiciness. An aggressively charred barrel will round a corn whisky making it silky.

The 9.09% Rule Clarified and Put to Bed

When Canadian whisky is the subject, someone from the back of the room pipes up, “You put fruit juice in your whisky!”, then bolts out a side door while the audience gathers torches and pitchforks. Let’s set the record straight. Canadian whisky cannot add whatever it pleases. The rule originally aided American producers. If they put a splash of American-made spirit in the whisky, they got a tax break when it crossed the border. Regardless, if a whisky does contain additional flavoring spirit, it must age for at least two years in wood. It’s a seldom exercised rule that has become an annotation at the back of the Canadian whisky playbook—with exceptions.

Alberta Distillers / Photo Credit: Blair Phillips

Alberta Distillers / Photo Credit: Blair Phillips

Think of the 9.09% rule as a superpower that Canadian whisky has over other categories. If used, a master blender will use it for good and not for evil. Alberta Premium Dark Horse (aka Alberta Rye Dark Batch) exercises its 9.09% right by adding approximately 8% Old Grand-Dad Bourbon and some sherry spirit to the blend. It has evolved into a secret weapon many bartenders use for high-end cocktails. J.P. Wiser’s Union 52 wouldn’t have existed if it weren’t for this rule. This blend contains 4% 52 year-old single malt Scotch. It’s a splash that adds layers of eyebrow raising complexity to the blend.

Now, it’s time to get out there and find your favorite Canadian whisky.

With Distiller, you’ll always know what’s in the bottle before you spend a cent. Rate, Review, and Discover spirits! Head on over to Distiller, or download the app for iOS and Android today!